In the Bambara language, baara means “work.” In Mali, however, this word goes beyond its simple translation: it is daily toil, lack of choice, support for families, the driving force of neighborhoods. It is the commitment that allows people to move forward and build their future, even under the hardest conditions – especially in a country that has been experiencing internal conflicts for more than 13 years.

Training in mechanics, Centre de Formation Professionnelle de Sénou, partner of the NGO WeWorld for a project on access to employment and social inclusion for young people, funded by Italian Cooperation. Bamako, May 2025

Alhabiboulaye and Mahamane work delivering crates of water for the Chinese-owned company Ooolala, using electric scooters. Bamako, May 2025.

One of Bamako's main landfills, where many people work sorting and transporting waste. Behind the university hill, Bamako. May 2025

Kassim Kouyaté works in the production of filtered drinking water bags.

Bamako, May 2025

Bamako, May 2025

Makeup training, Baron Centre, partner of the NGO WeWorld for a project on access to the world of work and social inclusion for young people, funded by Italian Cooperation. Bamako, May 2025

In Bamako, the vast capital of more than 3.2 million people, life pulses through speeding motorbikes, sotrama—the shared minivans weaving across dusty roads—and markets alive with color, scent, and sound. Work is everywhere: hands braiding hair and weaving cloth, repairing engines, cooking, selling, planting, fixing. In beauty parlors and craft workshops, in computer classes and vocational schools, young people are busy inventing and reinventing their trades.

Ninety-five percent of the city’s economy is informal: about 2.6 million men and women who come up with ways every day to earn just enough to make it to the next. Informality is anything but marginal — it’s organized, passed down from generation to generation, and it’s the true beating heart of Malian society.

Ninety-five percent of the city’s economy is informal: about 2.6 million men and women who come up with ways every day to earn just enough to make it to the next. Informality is anything but marginal — it’s organized, passed down from generation to generation, and it’s the true beating heart of Malian society.

Fatima Perou sells bunches of bananas on the streets of Bamako. May 2025

Sewa Barry has been living in the Sénou camp for displaced persons for seven years. From time to time, he collects trash or sells milk produced by the animals in the camp. However, most of the time he is unemployed and takes care of his ten children. Bamako, May 2025

Boucar Barry has been living in the Sénou camp for displaced persons for six years. He cultivates a small plot of land within the camp, which provides him with enough food to feed his ten children. Bamako, May 2025

Oumar Tapp has been living in the Sénou camp for displaced persons for seven years. He raises livestock, feeding them cotton waste. Bamako, May 2025

Hadia Dallo lives in the camp for displaced persons in Sénou. During the rainy season (July-August), she spends her time harvesting corn in the fields surrounding the camp. The rest of the year, she takes care of her household and her four children. Bamako, May 2025

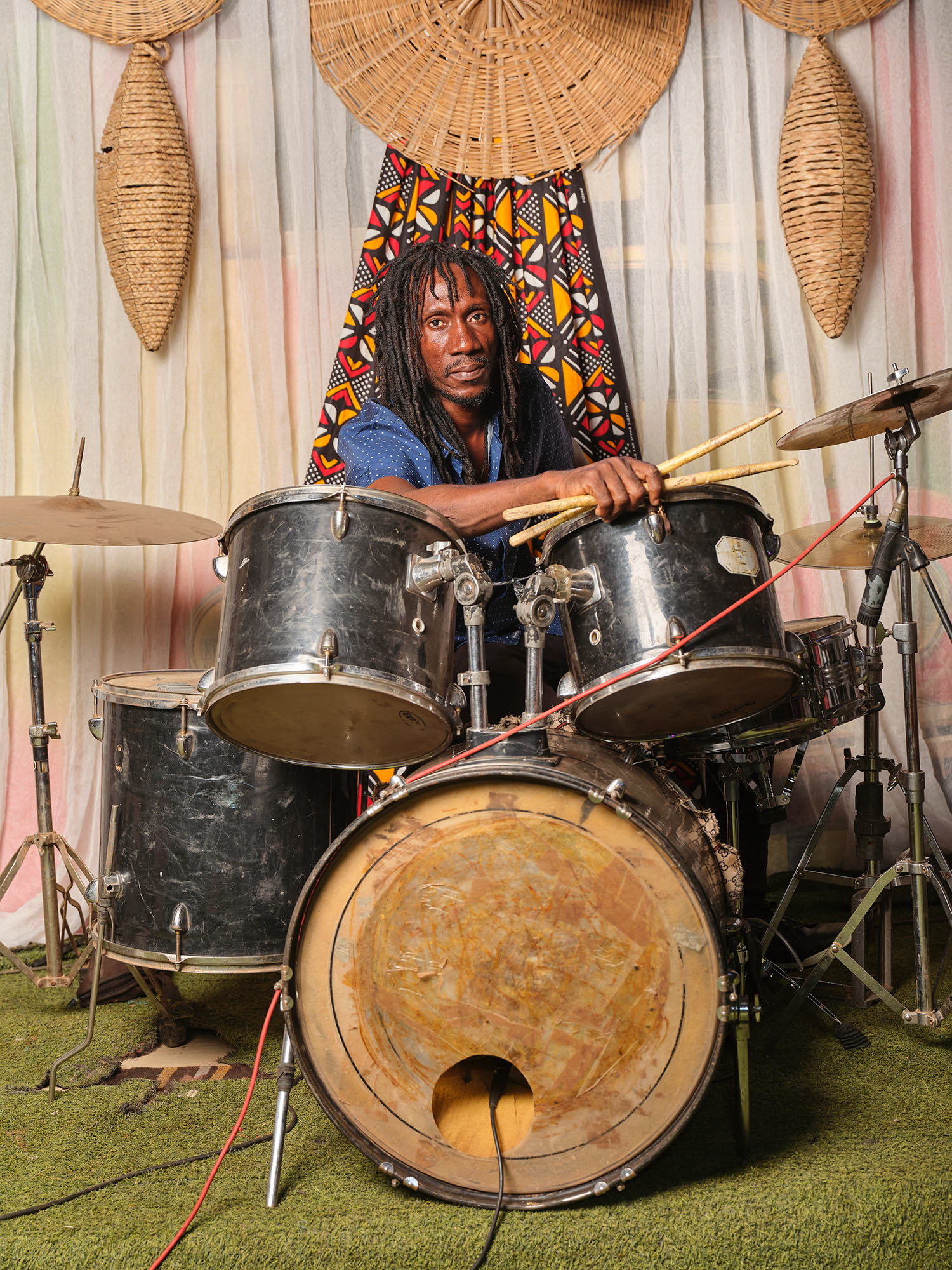

Moussa Balla Diallo plays drums with his band at Radio Libre in Bamako. During the day, he supplements his income by driving for the Heetch app. Bamako, May 2025

Badadere Daouda, captain of a pirogue on the Niger River, where he organizes sunset tours for groups. Bamako, May 2025

Rebeka Fojo and her son live in the Faladié displacement site, located on top of a garbage dump. She has a small stall where she sells food inside the site. Bamako, May 2025

Coulibaly Zean started his business selling grilled meat on the streets of Bamako, for which he received financial support from the project funded by the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation, implemented by the NGOs WeWorld, LVIA, and CISV. Bamako, May 2025

Elisabeta and Aminata work at the Baron Center beauty salon. Bamako, May 2025

These objects represent the various occupations encountered in Bamako:

the fly swatter for cooking, the knife for cutting meat, the sewing machine for training sessions,

the paper dress used to practice tailoring, the hair for braiding, the scale for weighing bunches of bananas,

the hoe for cultivating the garden in the Sénou site, the plastic waste to be sorted,

the spice bags sold in the Faladié site, and the glove used to produce organic charcoal.

the fly swatter for cooking, the knife for cutting meat, the sewing machine for training sessions,

the paper dress used to practice tailoring, the hair for braiding, the scale for weighing bunches of bananas,

the hoe for cultivating the garden in the Sénou site, the plastic waste to be sorted,

the spice bags sold in the Faladié site, and the glove used to produce organic charcoal.

One of the few informal shops in the Mabilé displacement site, which was set up in May 2019 in an old school building that went bankrupt following arson attacks at the Faladié site. Today, around 570 people live there.

Site for displaced persons from Mabilé seen from above, established in May 2019 in an old school building that went bankrupt following arson attacks at the Faladié site. Today, around 570 people live there.

Sewing training, Centre de Formation Professionelle de Missabougou, partner of the NGO WeWorld for a project on access to employment and social inclusion for young people, funded by Italian Cooperation. Missabougou neighbourhood, Bamako, May 2025.

Since 2012, Mali has been gripped by a multifaceted crisis that weaves together political instability, conflict, terrorism, and climate change. Droughts and floods have made life in rural areas even more precarious and, combined with widespread violence, have forced thousands of families to move to the cities. Today, more than 3,600 internally displaced people live in Bamako, trying to rebuild their lives in conditions that are often fragile, where finding work is a daily struggle. On the outskirts, some manage to sell small harvests from the surrounding land; in the heart of the city, others survive by sorting through waste to earn a little money. Amid this tangle of unemployment, rural exodus, and the arrival of displaced people—compounded by the lack of vocational training opportunities—access to work has become a true structural emergency. Equally urgent is the absence of urban planning and waste management systems to support the city’s growing population.

The streets of Bamako are very busy and only the main avenues are paved. Avenue Al Qoods, Bamako, May 2025

Exhibition, WeWorld Festival Bologna

Training in electronics, Centre de Formation Professionnelle Missabougou, partner of the NGO WeWorld for a project on access to employment and social inclusion for young people, funded by the Italian Cooperation. Missabougou district, Bamako, May 2025

Sidibe Bamadou is the director of an association that works to create jobs in the waste recycling sector. Bamako, May 2025

Guidance Desk in the Magnambougou district, created through WeWorld’s project funded by the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation on access to employment and social inclusion of young people in Bamako: a space where young people can go to receive guidance and support in their job search.

Alama Diakite, a bogolan artisan, works with traditional Malian fabrics dyed using plants and earth. He sells the textiles he produces from his home, where he also holds workshops for those who wish to learn the craft. Bamako, May 2025

Training in computer science, Maison de Jeunes, partner of the NGO WeWorld for a project on access to employment and social inclusion for young people, funded by the Italian Cooperation. Bamako, May 2025

Hawa, Batoma, and Fati live in the displacement site of Faladié, located on top of a waste landfill. They collect and sort plastic waste by color. Bamako, May 2025

These objects represent the various occupations encountered in Bamako:

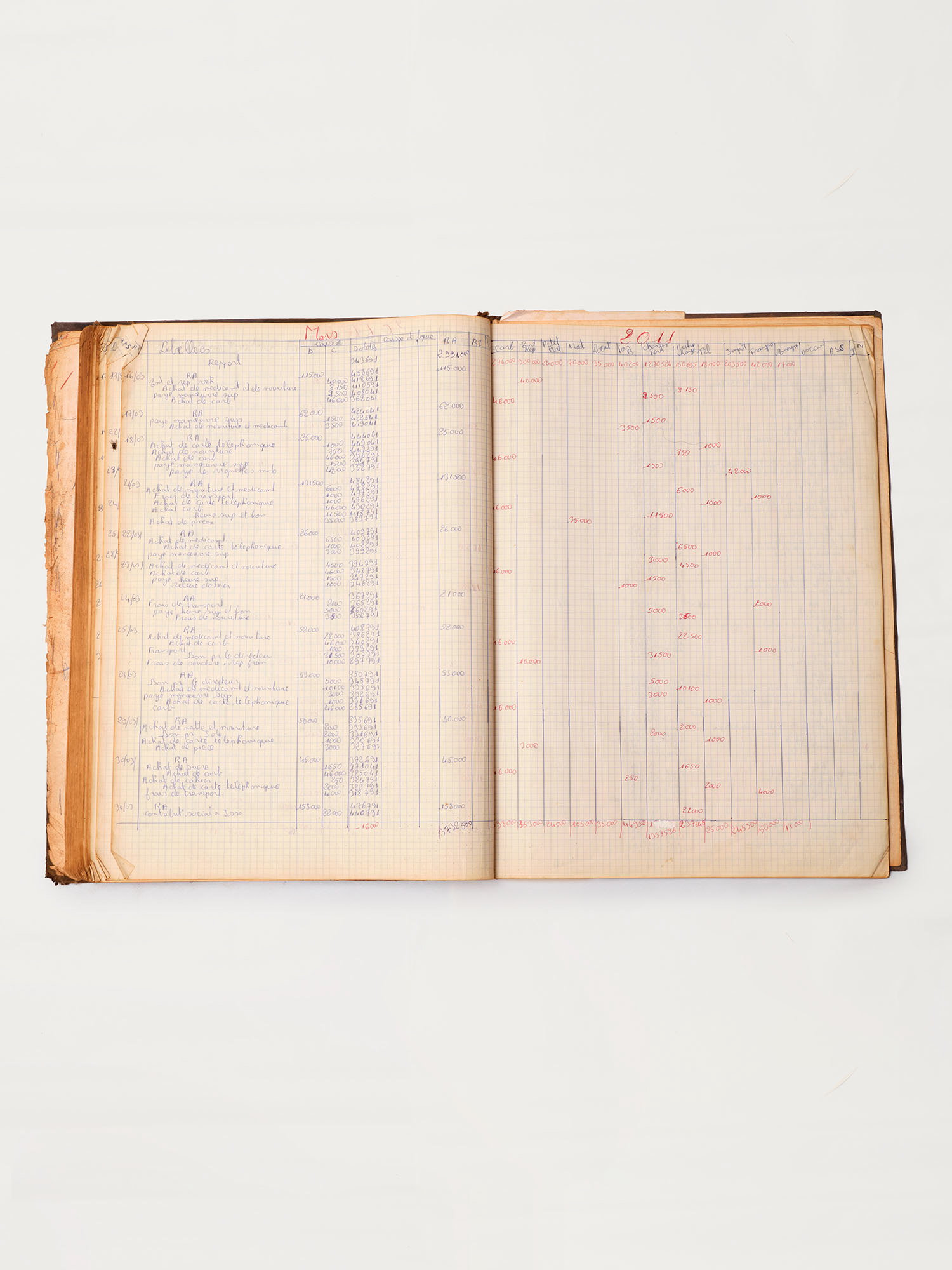

the magnet used in electronics training, the paintbrushes made from lollipop sticks to paint fabrics with earth, the drumsticks for playing music, the wrench for mechanical training, the animal feed from the Sénou field, the register of Mr. Bamadou’s association, the makeup used during training sessions, the certificate of participation from WeWorld’s training programs, the register of residents from the Mabilé site, the string used for measuring during construction training, the cardboard samples for henna tattoos, and the small bags of filtered drinking water.

the magnet used in electronics training, the paintbrushes made from lollipop sticks to paint fabrics with earth, the drumsticks for playing music, the wrench for mechanical training, the animal feed from the Sénou field, the register of Mr. Bamadou’s association, the makeup used during training sessions, the certificate of participation from WeWorld’s training programs, the register of residents from the Mabilé site, the string used for measuring during construction training, the cardboard samples for henna tattoos, and the small bags of filtered drinking water.

The main street of the “Marché des condiments” (spice market) in Bamako. May 2025

In Bamako’s Commune VI—the district with the youngest and largest population in the city—housing density is extremely high, especially in neighborhoods like Sogoniko and Faladié. The influx of displaced people here is the greatest, with more and more makeshift settlements and structural emergencies to confront.

BAARA portrays the residents of Commune VI in April 2025. Behind the numbers are individual stories: a musician who drives a taxi by day to make ends meet; a woman producing organic charcoal from household waste; a man teaching the art of dyeing traditional fabrics with plants and soil; young people reinventing themselves as influencers during make-up lessons. Each encounter is unique, valuable, illuminating.

Through his images, Baara brings to light the dynamics, gestures, and ambitions that rarely find space in narratives about Mali, yet are its true life force. Here, work is not just a means of survival—it is an act of resilience, a daily construction of the future.

Training in construction, Centre de Formation Professionnelle de Missabougou, partner of the NGO WeWorld for a project on access to employment and social inclusion for young people, funded by the Italian Cooperation. Missabougou district, Bamako, May 2025

Salimata works in the plastic waste division and in the production of organic charcoal made from organic waste. Bamako, May 2025

Bocar has been a sewing instructor at the Maison de la Femme for 4 years. He learned the craft by attending a course at the Centre de Formation Sénou., Bamako, May 2025

Training on henna tattoos, Centre de la Femme, partner of the NGO WeWorld for a project on access to employment and social inclusion for young people, funded by the Italian Cooperation. Bamako, May 2025